Description

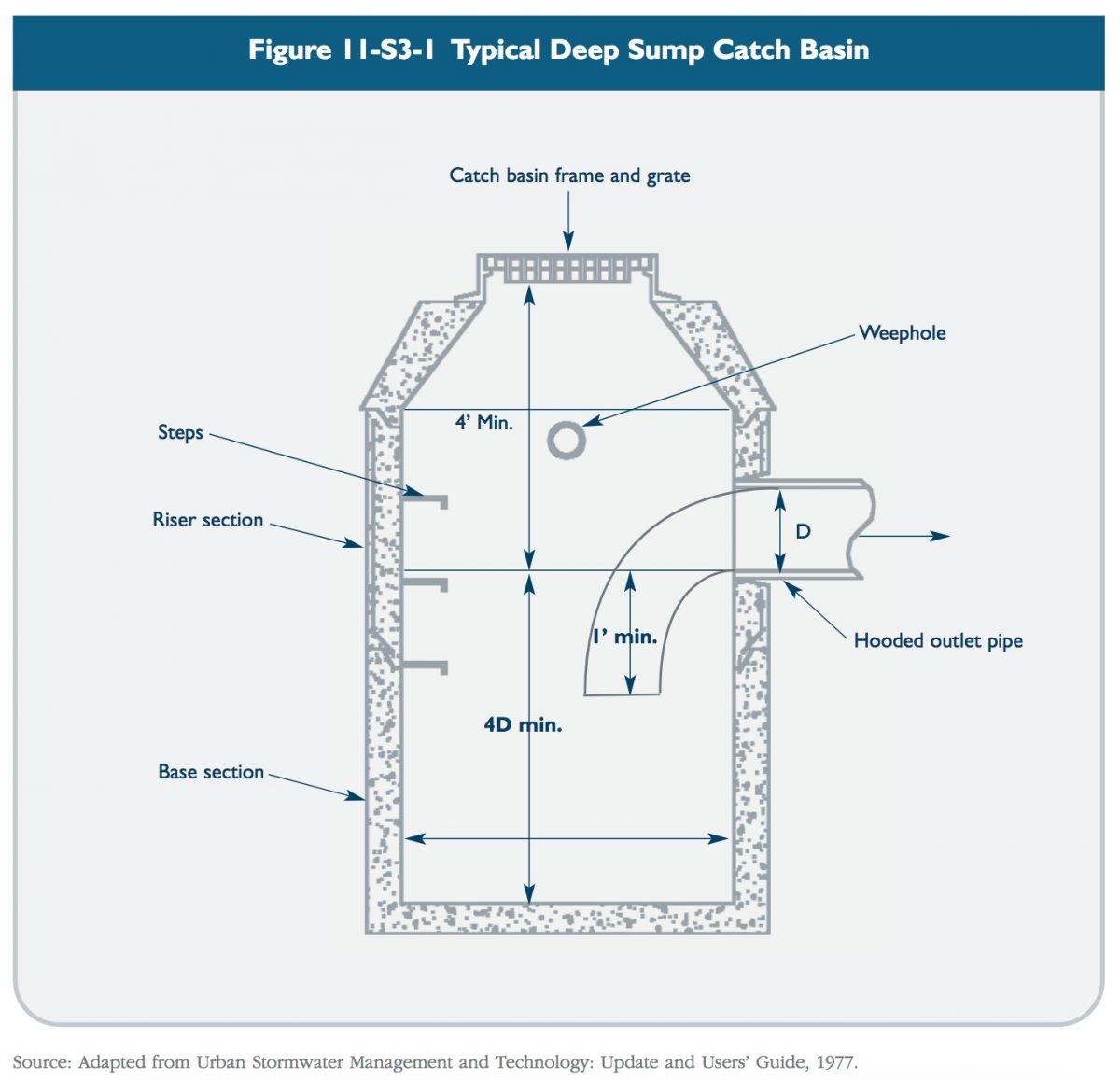

Deep sump catch basins, also known as oil and grease catch basins, are storm drain inlets that typically include a grate or curb inlet and a sump to capture trash, debris and some sediment and oil and grease. Stormwater runoff enters the catch basin via an inlet pipe located at the top of the basin. The basin outlet pipe is located below the inlet and can be equipped with a hood (i.e., an inverted pipe). Floatables such as trash and oil and grease are trapped on the permanent pool of water, while coarse sediment settles to the bottom of the basin sump. Figure 11-S3-1 shows a schematic of a typical deep sump catch basin.

Catch basins are commonly used in drainage systems and can be used as pretreatment for other stormwater treatment practices. However, most catch basins are not ideally designed for sediment and pollutant removal. The performance of deep sump catch basins at removing sediment and associated pollutants depends on several factors including the size of the sump, the presence of a hooded outlet, and maintenance frequency.

Reasons for Limited Use

Catch basins have several major limitations, including (EPA, 2002):

* Even ideally designed catch basins (those with deep sumps, hooded outlets, and adequate sump capacity) are far less effective at removing pollutants than primary

stormwater management practices such as stormwater ponds, wetlands, filters, and infiltration practices.

* Can become a source of pollutants unless maintained frequently.

* Sediments can be resuspended and floatables may be passed downstream during large storms.

* Cannot effectively remove soluble pollutants or fine particles.

* May become mosquito breeding habitat between rainfall events.

Suitable Applications

* For limited removal of trash, debris, oil and grease, and sediment from stormwater runoff from relatively small impervious areas (parking lots, gas stations, and other commercial development).

* To provide pretreatment for other stormwater treatment practices.

* For retrofit of existing stormwater drainage systems to provide floatables and limited sediment control. See Chapter Ten for examples of catch basin stormwater retrofits.

References

Ferguson, T., Gignac, R., Stoffan, M., Ibrahim, A., and J. Aldrich. 1997. Rouge River national Wet Weather Demonstration Project: Cost Estimating Guidelines, Best Management Practices and Engineered Controls. Wayne County, Michigan.

Lager, J., Smith, W., Finn, R., and E. Finnemore. 1997. Urban Stormwater Management and Technology: Update and User’s Guide. Prepared for U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA-600/8-77-014.

Pitt, R. and P. Bissonnette. 1984. Bellevue Urban Runoff Program Summary Report. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Water Planning Division. Washington, D.C..

Pitt, R.M., Nix, S., Durrans, S.R., Burian, S., Voorhees, J., and J. Martinson. 2000. Guidance Manual for Integrated Wet Weather Flow (WWF) Collection and Treatment Systems for Newly Urbanized Areas (New WWF Systems). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Office of Research and Development. Cincinnati, Ohio.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 1999. Preliminary Data Summary of Urban Storm Water Best Management Practices. EPA 821-R99-012.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2002. National Menu of Best Management Practices for Stormwater Phase II.

URL:http://www.epa.gov/npdes/menuofbmps/menu.htm, Last Modified January 24, 2002.

Water Environment Federation (WEF) and American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), Urban Runoff Quality Management (WEF Manual of Practice No. 23 and ASCE Manual and Report on Engineering Practice No. 87), 1998.